On June 2015 ACEP updated the 2013 policy on ischemic stroke treatment.

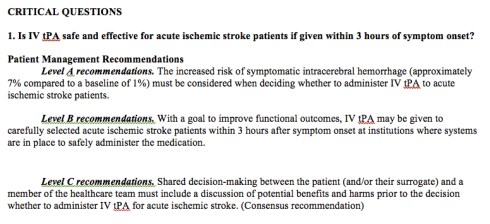

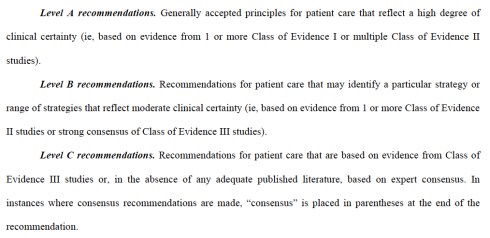

The 2013 policy graded the tPA administration within 3 hours as a Level A recommendation and tPA administration between 3 to 4.5 hours as Level B recommendation

In Jan 2015 ACEP published a Draft about the update of the 2013 clinical policy based on 2 critical questions:

-

Is IV tPA safe and effective for patients with acute ischemic stroke if given within 3 hours of symptom onset?

-

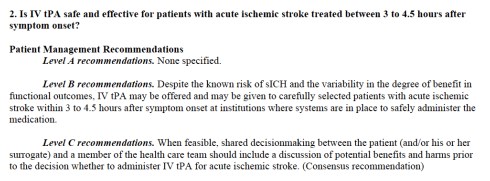

Is IV tPA safe and effective for patients with acute ischemic stroke treated between 3 to 4.5 hours after symptom onset?

In June 2015 the definitive policy was released, based on the same critical questions.

Here is the most relevant changes:

- TPA administration within 3 hours was graded as a Level B recommendation (NNT 8 with a 95% CI).

- The statement says that tPA “should be offered and may be given to selected patients” (“should be offered” alone in 2013 policy)

- In the same Level B recommendation was incorporated consideration (that in the previously Jan Draft was Level A) about sICH risk (7% with a NNH of 17 and 95%CI).

- TPA administration between 3 and 4.5 hours is still considered a Level B recommendation (NNT=14; 95% CI). The the risk of early sICH in this case correspond to a NNH of 23 (95% CI)

- The recommendation statement begins mentioning and prioritizing the “known risk of sICH and the variability in the degree of benefit in functional outcomes”, and about tPA treatment says “may be given to carefully selected patients” (“should be considered” in in 2013 policy)

Some considerations on evidences supporting the recommendations in this 2015 policy:

- TPA administration within 3 hours is supported by just 1 Class I study (NINDS part 2, 1995), a small study (n.333 ) that despite the benefit on functional outcomes, demonstrate no statistically significant difference in 3-month mortality, and was never been replicated.

- All the sub-analysis from NINDS study where considered of Class II or III evidences.

- ECASS III study was downgraded (from 2013 policy) to a Class II evidence study cause of “baseline differences between groups and changes in the timing of tPA administration during the course of the study”.

- IST-3 study is graded as a Class III study.

- TPA Administration between 3 and 4.5 hours is supported just by 1 Class II study and some other Class III case series.

What I like about the policy:

- Level B recommendation for tPA administration within 3 hours is fair enough

- The panel who examined the available litterature put the right light on controversies and conflict of interest involved in most of the recent studies (ATLANTIS, IST-3, ECASS ecc…) and following statistical analysis, grading most of them as Class III evidences, and leaving as Class I just NINDS part 2 (a 1995 study who yes demonstrate benefit on functional outcome but no difference in 3 months mortality, is a small study and has never been reproduced) .

What I don’t like about the policy:

- Level B recommendation for tPA administration between 3 and 4.5 hours is too high cause is supported just by 1 Class II study (ECASS III) and a bunch of Class III evidences.

- The authors in their final statement play with terms jumping between “should be offered and may be given” and “selected patients” for 3 hours treatment to “may be given” and “carefully selected patients”for the 3 to 4.5 hours treatment, to emphasize the difference between recommendations both graded as Level B but supported by such a different quality of evidences. These leave to clinician a wide margin of discretionality (“may be given” but also “may be not”) supporting them in their choices (whatever it is, and that is good), but from the other hand not giving a clear advice or any clinical tool to help the decision making process. This gonna result in a large variability of approach.

- The risk of sICH is the only demonstrated and consistent evidence that appears trough the letterature in those years and is not clear why in the draft of Jan 2015 was classified as Level A and in the definitive policy was relegated as Level B with no new evidences added in the meantime, and no clear explaination.

Bottom line

I think thrombolysis is a beneficial treatment for a selected group of patients. The available evidences and policies (even this last one) based on time window alone, and not patient centered, don’t clearly indicate which group of patients really benefits from tPA administration.

This 2015 ACEP policy suggests physician to strongly consider the risk (evident)/benefit (maybe) ratio when offering tPA in acute ischemic stroke and to strongly involve patients in the final decision. It also leave the clinician a wide range of choice to decide which is the right patient to treat with tPA.

“When considering administration of IV tPA for a patient with acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours of stroke symptom onset, the physician and patient (and/or the surrogate) should weigh the potential benefit in terms of long-term functional outcome against the increased risk of sICH while recognizing that IV tPA does not alter 90-day mortality.“

Important readings:

References:

- 2013 Clinical Policy: Use of Intravenous tPA for the Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Emergency Department

- Clinical Policy: Use of Intravenous tPA for the Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Emergency Department DRAFT January 5, 2015

- Clinical Policy: Use of Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator for the Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Emergency Department Approved by the ACEP Board, June 24, 2015

Unmissible resources:

Load-Play-Go in Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest. The “6 minutes approach”.

29 LugIn the Prehospital Emergency System where I work (from late 1996) we are historically used to manage cardiac arrest events with a deep “Stay and Play”, except for some sporadic cases (mostly pediatric patients) . The rising of A-V ECMO era (and in Florence there is a major ECMO center) and lastly of mechanical chest compression devices, took us to rethink the whole approach to the management of cardiac arrest.

Is there now a role for a “Load-Play and Go” approach in some selected patients.

Let’s try to figure out some of the major challenges that this new approach can pose to emergency physician working in a prehospital environment.

Wich is the right patient

The all V-A ECMO process is a really expensive stuff in term of both, human and financial resources. So the development of criteria to predict wich patient is potentially a candidate to good neurological outcome is oriented to spare money (for the collectivity) and to avoid futility (for the patients).

For sure a relatively young age, and the absence of invalidant comorbidities can play a role in these decision. But also the “no flow” time, intended as the time from when the CA happened to the start of chest compressions in the witnessed CA and a shockable rythm finding or a potential reversible cause in non witnessed CA are sign of predictable good outcome.

The V-A ECMO, last but not least, needs a strict time schedule from the CA to the cannulation process to be effective and so the transport time to ECMO Center plays also a fundamental role in the decision making.

Putting all together these specification we can, with a good approximation, describe the right candidate for External Cardiac Life Support (ECLS).

But what about the pratical approach to those patients. Is still the classical ALS protocol the way to follow?

The six minutes approach to Load-Play and Go in OHCA

The basic skills are not different, but the real difference is the mind of the resuscitationist (S. Weingarth dixit) in these cases.

If you already decided this is the right patient the right time, we propose a six minute approach to manage all the features you need to perform in the first phase of a OHCA before “loading” the patients, “playing” during the “going” phase toward ECMO Center.

Condividi: