PreOxygenation

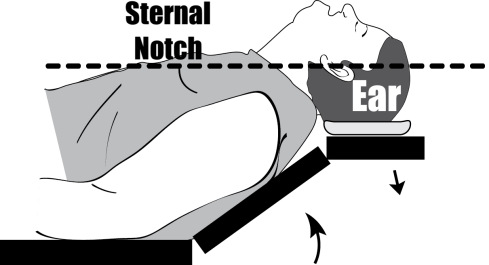

Positioning

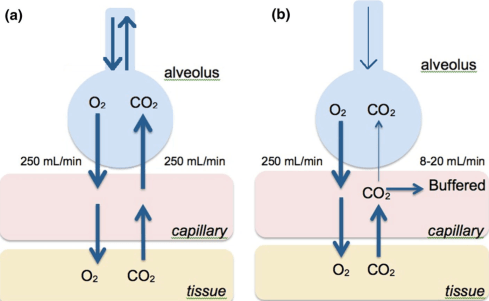

Apneic Oxygenation

Direct Laryngoscopy

Video Laryngoscopy

STAY BACK

STAY LOW

Bougie First

For who has a multiyear experience in prehospital emergency medicine and deals everyday with emergency transportation of critical patients the sensation is that the use of emergency warning systems are, mostly of times, useless and doesn’t really have any impact on clinical outcomes.

But beyond any subjective thought, do we have any evidence on that?

My analysis starts from this article published in 2018 on Annals of Emergency Medicine

by Brooke L. Watanabe, MD et al. and entitled “Is Use of Warning Lights and Sirens Associated With Increased Risk of Ambulance Crashes? A Contemporary Analysis Using National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) Data”. The authors conclusion says that “Ambulance use of lights and sirens is associated with increased risk of ambulance crashes. The association is greatest during the transport phase. EMS providers should weigh these risks against any potential time savings associated with lights and sirens use.“

Curbside to Beside blog published an interesting post about this topic and resumed the data in this incredibly intuitive infographic

While ambulances crash rate when using L&S (light and sirens) in the response phase is slightly increased (7.0 vs 5.4) in the transportation phase the amount of crashes associated with L&S use is significatively higher (17.1 vs 7.0).

So L&S transportation increases the odd of crash (and this is intuitive) but, on the other side, is there any evidence that use of L&S increases response time and improve clinical outcome?

Fabrice Dami et al in an article entitled “Use of lights and siren: is there room for improvement?” found that the time saved with L&S transport was 1.75 min (105 s; P<0.001) in day time and 0.17 min (10.2 s; P=0.27) night-time.

So evidently fast is time, but is a gain of less than 2 min a clinical significative time?

In 2010 in the article “Emergency Medical Services Intervals and Survival in Trauma:Assessment of the “Golden Hour” in a North AmericanProspective Cohort” concluded that “there was no association between EMS intervals and mortality among injured patients with physiologic abnormality in the field”.

Anderson et al in a 2014 article “Preventable deaths following emergency medical dispatch – an audit study” demonstrated how just 0,2% of the 94.488 “non L&S” dispatched emergencies died in the first 24 hours from the call. Of those just 0.02% of total “non L&S” emergencies were considered “potentially preventable if the dispatcher had assessed the call as more urgent and this had led to an ambulance dispatch with a shorter response time and possible rendezvous with a physician-staffed mobile emergency care unit”

So mostly of the emergencies are not time sensitive and the clinical outcome does not differ if the transport time is shorter.

Maybe we need lights and sirens in response phase, cause slightly increase in accident risk corresponds to some gain in arriving time on the scene.

Maybe we don’t need lights and sirens in transportation phase cause a great increase in risk of crash do not correspond to a clinical sensitive time gain.

For sure when using L&S we need to be aware that the risk doesn’t worth the price, and even if we use L&S in the varies phases of emergencies pushing the threshold of security too forward increases the risks and don’t improve clinical benefits for the transported patients.

Clinicians need to be more concerned about performing the right procedures to stabilise patients on pre-hospital phase more than hurrying with unstable patients toward an unreal Eldorado and risking their own and patients lives.

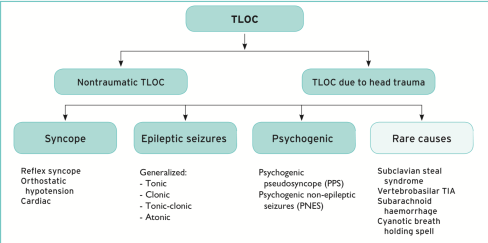

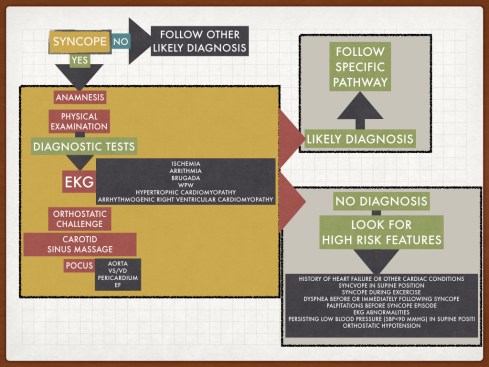

Non traumatic Transitory Lost Of Consciousness (TLOC) is a common cause of medical emergency call. Among TLOC Syncope is the most common cause. So the first challenge for an emergency professional is discerning from Syncope and non syncope situations (seizures, psychogenic, other rare causes).

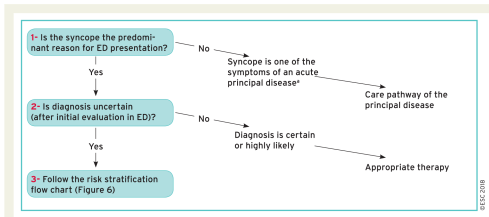

2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope

Syncope according to 2018 Guidelines definition is a “TLOC due to cerebral hypoperfusion, characterised by a rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery”.

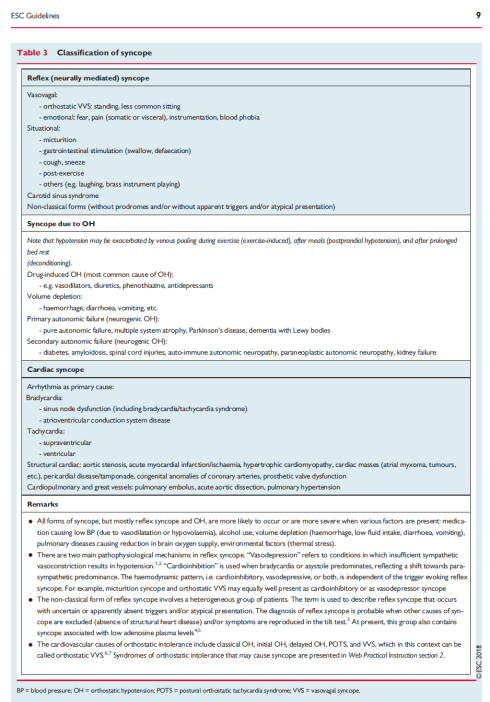

Among Syncope the causes can be found in vagal reflex (Reflex syncope), a drop in blood pressure due to a deficiency of compensation in a standing position (Orthostatic syncope) and a cardiac cause of syncope (Cardiac syncope)

2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope

But what is the role and what can and must be done on the prehospital field to understand treat and risk stratify a Syncope?

Is a fundamental step to understand and risk stratify a syncope episode. It has to be targeted to collect all the important informations and to don’t loose precious time.

We can divide the information we collect in two categories.

The first kind of information we area going to ask (to bystanders and patients) is about the syncope event.

Second step is collecting informations about the patient medical conditions. We have to focus on

After a focus anamnesis the second step is about the physical exam of the patient.

During physical exam a rapid general neurologic and cardiac examination has to be completed, but two additional steps need to be done in a syncope patients

Orthostatic challenge: Standing BP evaluation has to be done after 3 minutes of active standing position with the patient fully monitored, and “abnormal BP fall is defined as a progressive and sustained fall in systolic BP from baseline value >_20 mmHg or diastolic BP >_10 mmHg, or a decrease in systolic BP to <90 mmHg” (European Society of Cardiology 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope).

Carotid sinus massage: A ventricular pause lasting >3 s and/or a fall in systolic BP of >50mmHg is known as carotid sinus hypersensitivity. “Carotid sinus syndrome (CSS) There is strong consensus that the diagnosis of CSS requires both the reproduction of spontaneous symptoms during CSM and clinical features of spontaneous syncope compatible with a reflex mechanism.” (European Society of Cardiology 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope)

12 leads EKG

It’s a fundamental diagnostic tool and has to be performed in all syncope patients.

What are the risky features we have to consider when looking to ann EKG of a syncope patients:

At least 6:

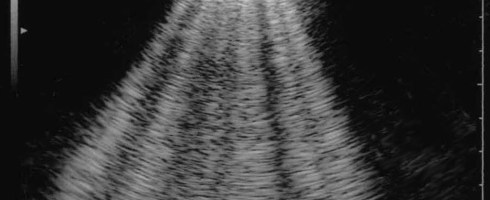

POCUS

Is there a role for Point of Care Ultrasound in differential diagnosis and risk stratification of syncope.

Probably yes cause we can look at:

At the end of those steps the prehospital professional has two chances.

2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope

If the cause is known or very likely we have to follow the specific pathway.

In the unknown syncope we have to stratify the risk.

In prehospital field is important to look for high risk features of syncope:

Each one of those is indicative of high risk prehospital features and the patient need further ED examination.

In all other cases the clinician can decide case by case if the patient can be treated out of the hospital or need admission to ED.

References :

Rapid Sequence Intubation in Traumatic Brain-injured Adults

Management of traumatic brain injury patients

Pediatric traumatic brain injury—a review of management strategies

Traumatic arrest & the HOTTT Drill

Prehospital Plasma during Air Medical Transport in Trauma Patients at Risk for Hemorrhagic Shock

Evaluation of tranexamic acid in trauma patients: A retrospective quantitative analysis

Prehospital haemostatic dressings for trauma: a systematic review

Pediatric airway management devices: an update on recent advances and future directions

Pre-hospital emergency anaesthesia in awake hypotensive trauma patients: beneficial or detrimental?

Damage Control for Vascular Trauma from the Prehospital to the Operating Room Setting

Issues and challenges for research in major trauma

Pre-hospital i-gel blind intubation for trauma: a simulation study.

Supraglottic airway devices: indications, contraindications and management.

Endotracheal Intubation for Traumatic Cardiac Arrest by an Australian Air Medical Service.

Airway Management During Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Interpreting the Cormack and Lehane classification during videolaryngoscopy.

Intubation with cervical spine immobilisation: a comparison between the KingVision videolaryngoscope and the Macintosh laryngoscope. A randomised controlled trial.

Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults.

Airway Management for Trauma Patients

Pragmatic Airway Management in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Implementation of a Clinical Bundle to Reduce Out-of-Hospital Peri-intubation Hypoxia

The Vortex model: A different approach to the difficult airway

Defining the criteria for intubation of the patient with thermal burns

Shifting Priorities from Intubation to Circulation First in Hypotensive Trauma Patients

Pediatric airway management devices: an update on recent advances and future directions

Rapid Sequence Intubation in Traumatic Brain-injured Adults

Liberally adapted from:

References:

Myth #1

Myth #2

Myth #3

Myth #4

Myth #5

So 2018 is at the end and we give, as every year, a look back to literature and articles of this finishing year.

This is the first step of 1 YEAR IN REVIEW the classical MEDEST appointment with all that matter in emergency medicine literature.

So let’s start with Guidelines but first I want to cite an important point of view about Clinical practice Guidelines and they future development:

“Clinical practice guidelines will remain an important part of medicine. Trustworthy guidelines not only contain an important review and assessment of the medical literature but establish norms of practice. Ensuring that guidelines are up-to-date and that the development process minimizes the risk of bias are critical to their validity. Reconciling the differences in major guidelines is an important unresolved challenge.”

Paul G. Shekelle, MD, PhD. Clinical Practice Guidelines What’s Next?

Should we withhold chest compressions in traumatic cardiac arrest. A (very) reasonable poin of view.

‘Don’t compress the chest in traumatic arrest…’ That’s the narrative. But Alan Garner has questions.

Do you do chest compressions in traumatic cardiac arrest (TCA)?

Don’t be dopey, right? Compressions are not important compared with seeking and correcting reversible causes. Indeed you can just omit the compressions altogether and transport the patient without them as they are detrimental in hypovolaemia and obstructive causes of arrest, right?

I would like to work through the logic of this. I think the nidus of an idea got dropped into a super saturated FOAMEd solution and Milton the Monster* precipitated out. The end result might be an approach that got extrapolated way beyond the biologically plausible.

The Starting Point

First let’s try to step slowly through the logic…

View original post 1,100 more words

Supporting ALL Ohio EM Residencies in the #FOAMed World

Let's try to make it simple

a blog for thinking docs: blending good evidence, physiology, common sense, and applying it at the bedside!

More definitive diagnosis, better patient care

Reviewing Critical Care, Journals and FOAMed

Prehospital critical care for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Education and entertainment for the ultrasound enthusiast

A UK PREHOSPITAL PODCAST

Emergency medicine - When minutes matter...

Sharing the Science and Art of Paediatric Anaesthesia

"Live as if you will die tomorrow; Learn as if you will live forever"

Navigating resuscitation

A Hive Mind for Prehospital and Retrieval Med

Thoughts and opinions on airways and resuscitation science

A Free Open Access Medical Education Emergency Medicine Core Content Mash Up

Rural Generalist Doctors Education

Emergency Medicine #FOAMed

این سایت را به آن دکتوران و محصلین طب که شب و روز برای رفاه نوع انسان فداکاری می کنند ، جوانی و لذایذ زندگی را بدون چشمداشت به امتیاز و نفرین و آفرین قربان خدمت به بشر می کنند و بار سنگین خدمت و اصلاح را بدوش می کشند ، اهداء می کنم This site is dedicated to all Doctors and students that aver the great responsibility of People’s well-being upon their shoulders and carry on their onerous task with utmost dedication and Devotionاولین سایت و ژورنال انتــرنتی علـــمی ،تخـصصی ، پــژوهشــی و آمــوزشــی طبـــی در افغــانســـتان

PHARM, #FOAMed

Free Open Access Medical Education

Learning everything I can from everywhere I can. This is my little blog to keep track of new things medical, paramedical and pre-hospital from a student's perspective.

In memory of Dr John Hinds

All you want to know about prehospital emergency medicine

Check out our updated blog posts at https://www.italycustomized.it/blog

The FOAM Search Engine

where everything is up for debate . . .

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Education

Free Open Access Medical Education for Paramedics

useful resources for rural clinicians

Unofficial site for prehospital care providers of the Auckland HEMS service

L'ECOGRAFIA: ENTROPIA DELL'IMMAGINE

Prehospital Emergency Medicine

Your Boot Camp Guide to Emergency Medicine

WE HAVE MOVED - VISIT WWW.KIDOCS.ORG FOR NEW CONTENT

Prehospital Emergency Medicine

Academic Medicine Pearls in Emergency Medicine from THE Ohio State University Residency Program

Prehospital Emergency Medicine

Prehospital Emergency Medicine

The Pre-Hospital & Retrieval Medicine Team of NSW Ambulance

Pulseless electrical activity following traumatic cardiac arrest: Sign of life or death?

11 JunOn May 2019 was published an article we review today, cause the authors conclusions are pretty astonishing and worth a deeper look.

Israr, S & Cook, AD & Chapple, KM & Jacobs, JV & McGeever, KP & Tiffany, BR & Schultz, SP & Petersen, SR & Weinberg, JA. (2019). Pulseless electrical activity following traumatic cardiac arrest: Sign of life or death?. Injury. 10.1016/j.injury.2019.05.025.

Authors Conclusions: Following pre-hospital traumatic cardiac arrest, PEA on arrival portends death. Although Cardiac Wall Motion (CWM) is associated with survival to admission, it is not associated with meaningful survival. Heroic resuscitative measures may be unwarranted for PEA following pre-hospital traumatic arrest, regardless of CWM.

What kind of study is this?

A retrospective, cohort study consisting of adult trauma patients (n. 277 patients ≥18 years of age) admitted to one of two American College of Surgeons verified level 1 trauma centers in Maricopa County, Arizona within the same hospital system between February 2013 to September 2017 and January 2015 to December 2017.

Pre-hospital management by emergency medical transport services was guided by advanced life support protocols.

Both hospitals for management of Traumatic Cardiac Arrest (TCA) followed the Western Trauma Association Guidelines

The following variables were collected from each patient:

Results

Outcomes

20 patients were identified on arrival to have had ROSC. 18 of these patients survived to hospital admission and 4 of them were discharged alive from hospital

147 patients were identified on arrival in asystole. Among these patients none were discharged alive from hospital.

The remaining 110 patients presented with PEA. 10 patients survived to admission, 9.1%, but only one, 0.9% was discharged from alive from hospital.

P-FAST was performed in 79 of the 110 patients with PEA (71.8%)

Presence of CWM was significantly associated with survival to hospital admission (2 but not to hospital discharge (zero with or without CWM).

Authors conclusions

My considerations on methodology and results

So in my opinion this study and it’s conclusions are biased by a wrong approach to Traumatica Cardiac Arrest in the prehospital phase.

Emergency providers, when treating patients in traumatic cardiac arrest, need to perform interventions addressing the possible REVERSIBLE causes:

Emergency providers need to rely on direct (central pulse palpation, Ultrasuond) or indirect (EtCO2, Plethysmography) signs of perfusion to guide their clinical interventions.

Resuscitation of Traumatic Cardiac Arrest patients in not futile just need to be performed in the right way.

References

Israr, S & Cook, AD & Chapple, KM & Jacobs, JV & McGeever, KP & Tiffany, BR & Schultz, SP & Petersen, SR & Weinberg, JA. (2019). Pulseless electrical activity following traumatic cardiac arrest: Sign of life or death?. Injury. 10.1016/j.injury.2019.05.025.

Share this: